If you read my post about my MSci research project, you’ll hopefully have learned a little bit about sexual selection… if you didn’t, why not go and check it out, it’s worth a read, I promise. Whilst doing some research for my project I came across a new journal article about female choice which could change the way we think about mate preferences and sexual selection and open doors to exciting new areas within this field of research.

The concept of female choice is widespread and well recognised within the fields of animal behaviour and evolution. The theory states that females mate non-randomly with males in order to improve their reproductive output or enhance the quality of their offspring and there is a huge amount of evidence to support this from studies on a wide range of species. However, this research has focused on preferences of entire populations and there hasn’t been much research into individual variation in preferences… until now. In February, Animal Behaviour published a paper by Castilho et al. (2020) which has shed new light on female mate preferences and how they shape sexual selection and potentially even speciation (the formation of a new and distinct species).

The jumping spider:

Castilho et al. (2020) explored sexual selection at the population and individual level in the tropical jumping spider, Hasarius adansoni (which sounds like it could be scary, but I think they’re probably the cutest spiders I’ve ever seen).

Many jumping spiders display complex mating displays… this famous clip from the most recent David Attenborough documentary (Seven worlds, One planet) was a species of jumping spider.

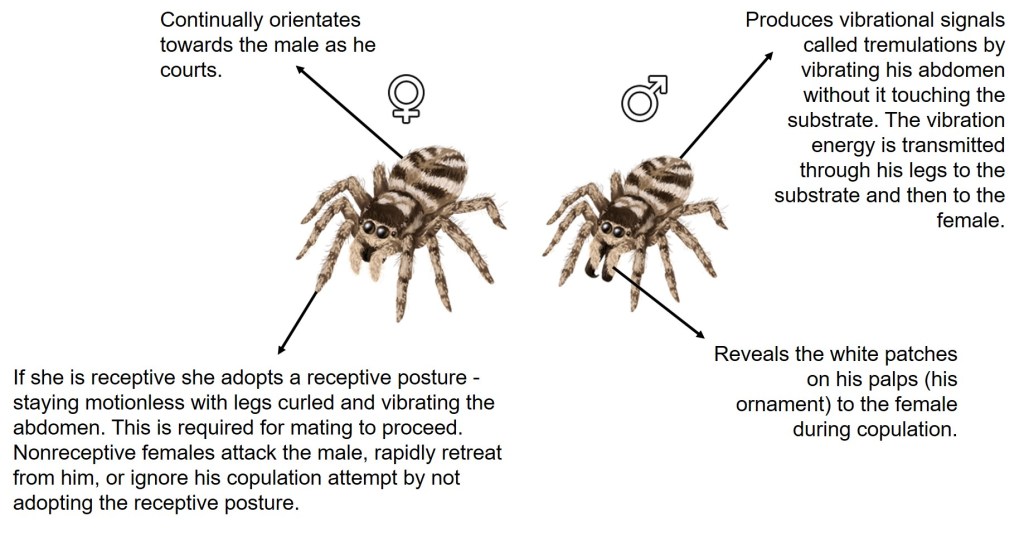

Hasarius adansoni exhibits courtship displays which include visual and vibrational signals, making them good model species for studying sexual selection.

What did Castilho and his colleagues do?

Their methodology was long and detailed so I’ve summarised the main points:

- They paired each female with a randomly assigned male to assess whether there was a population-level preference in females based on male size or ornament dimensions (ornaments are exaggerated characteristics which often display quality).

- After these mating trials, they kept females isolated until they produced eggs.

- They then counted the number of egg sacs per female and the number of hatched offspring per sac. Offspring were housed individually so that they could be used in offspring experiments.

- They compared offspring quality (a measure of feeding performance) and quantity to determine whether there were any benefits to female choosiness – in other words, to see if different males presented different benefits for females.

- Finally, they paired individual females with three different-sized males (small, average and large) in random order on three separate days (one male per day), to measure individual preference in females.

- They also assessed possible causes for individual preference variation by testing whether female mating experience or size influenced their sexual preferences.

They predicted that the females would display a population-level sexual preference because this species exhibits courtship displays, which usually implies some form of female choice. They also predicted that females would be more receptive to males which sire more and/or better-quality offspring (e.g. larger males).

What they found was really quite interesting:

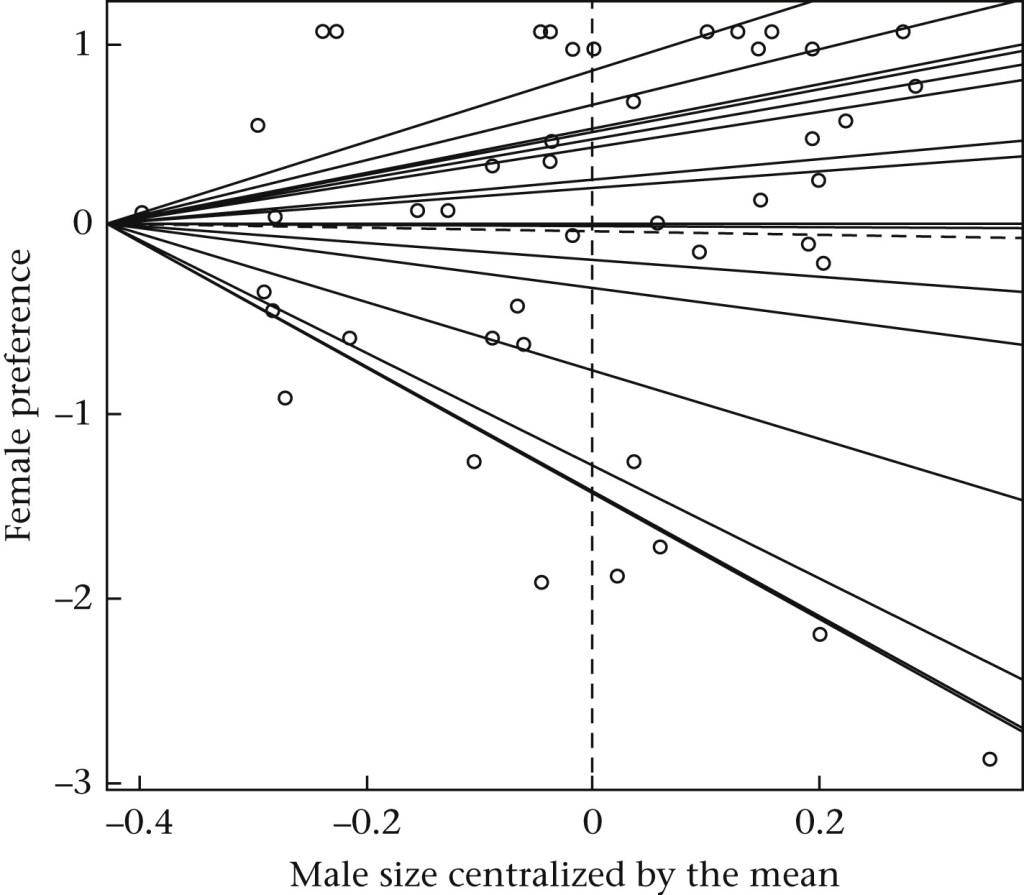

- Females did not prefer any particular male trait (mass, condition or percentage of white patch cover on the palps) at the population level, despite the fact that larger males produce more offspring.

- Individual females differed in how much they preferred different-sized males. Importantly these preferences ‘cancelled each other out’ at the population level because some preferred larger males while others preferred smaller males.

This led them to conclude that female preferences can be ‘masked’ if correlations are only measured at a population level!

Although they came to an important conclusion, there were a few limitations:

- The experimental conditions were stable but the conditions that each individual experienced whilst developing were unknown, meaning that not all test subjects had the same treatment.

- Analysis was poor and made too many assumptions – they used Principle Components Analysis (PCA) which means that they clumped variables together rather than analysing them separately.

- The paper was dense, wordy and hard to read in places, perhaps because it included several different tests and analyses. It could’ve been split into smaller studies which focused on a few of these tests at a time, allowing them to go into more detail and test the possible reasons for their findings.

Why does any of this matter?

This paper challenges previously accepted concepts in biology and could open the door to lots of new research in sexual selection. According to these results, mate preference is more versatile than previously thought and even when a population-level preference exists, individual preferences may also play an important role in the sexual selection and evolution of that species.

Hence, in the future, conclusions about sexual preferences should only be made when individual preferences are accounted for. Perhaps more striking is that this paper supports the concept that sexual selection may promote speciation, something which is heavily debated. Distinct female preferences help to maintain the genetic variation needed for speciation to occur (because females select different males with different genes, which are passed on to the next generation). Future studies which build on this publication could help us further understand the evolutionary importance of individual mate preferences.

On a more personal level, this paper has made me consider how individual preferences may affect the results of my Masters research, something which I will certainly be discussing in my project write-up.

Here’s the link to the original paper, if you want to give it a read: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0003347219303768

Comment below with any questions and/or ideas, and check out my blog ‘Is he hissy fit’ to find out more about my Masters project and why this paper is relevant to my research.

Recommended reading:

- Castilho, L. B., Macedo, R. H. & Andrade, M. C. B. (2020) Individual Preference Functions Exist without Overall Preference in a Tropical Jumping Spider. Animal Behaviour 160, 43–51.

- Chen, B., Liu, K., Zhou, L., Gomes-Silva, G., Sommer-Trembo, C. & Plath, M. (2018) Personality Differentially Affects Individual Mate Choice Decisions in Female and Male Western Mosquitofish (Gambusia Affinis). PLOS ONE 13, e0197197.

- Houde. A. E. (2001) Sex roles, Ornaments, and Evolutionary Explanation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 98, 12857-12859.

- Jones, A. G. & Ratterman, N. L (2009) Mate Choice and Sexual Selection: What Have We Learned since Darwin? Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106 (Supplement 1), 10001–10008.